Making the Disproportion of National Minorities Among War Victims in Ukraine

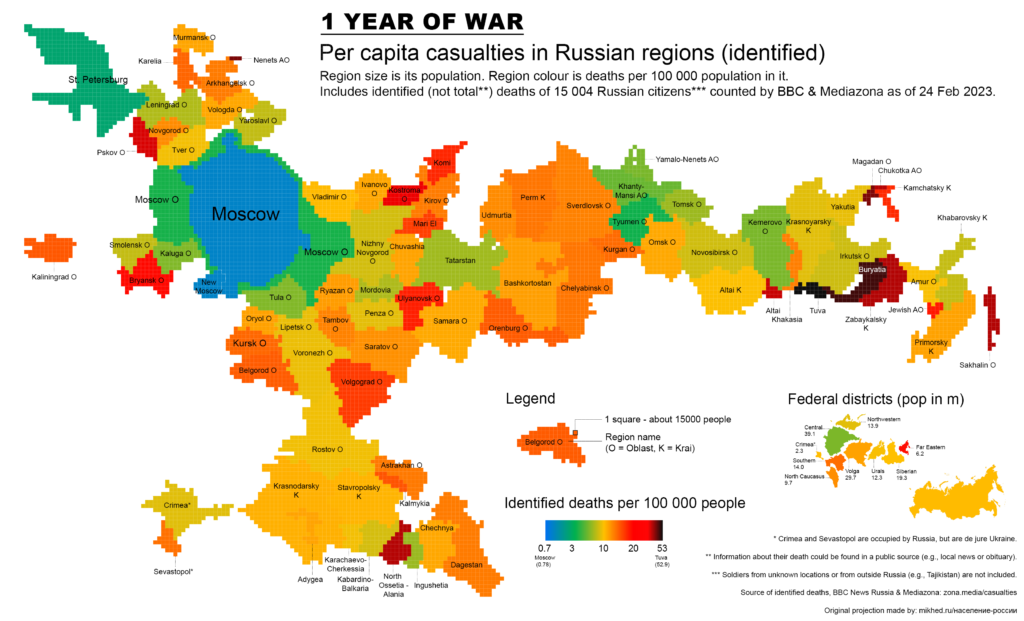

It should not be forgotten that the disproportion of national minorities among the victims of the war in Ukraine also plays a significant role. The scale of the problems and their accumulation depends on the region and social class concerned. However, the process is most severely affecting the poorest inhabitants of Russia’s provinces.

The Publicly Accused Wrongdoer

The Kremlin is often not the publicly accused wrongdoer for this state of affairs, or at least not yet. The role of a well-paid scapegoat here is played by a local baron, governor, administrator, or whatever you want to call them, appointed on Moscow’s behalf. This individual, thoroughly corrupt and driving the latest model Bentley, is believed to steal the money sent from Moscow. This is a popular image among Russian locals.

Moscow’s Control and the Local Baron

As long as Moscow signals that it is in control of the situation and the local baron has enough resources to maintain relative calm in the province, the system works. However, if the state of the local baron’s bank accounts does not drastically decrease, and public sentiment degrades, large-scale protests could emerge, and the situation for the local barons could become uncomfortable.

On one hand, they will be attacked, most often verbally, though perhaps also physically, by local people who will demand that they fulfill their local duties and regional loyalties. On the other hand, they will be pressured by the Kremlin, which expects regular transfers to the core and the suppression of unrest.

Temptation for Barons to Cut Ties with Moscow

In this scenario, particularly in resource and industrial regions, there may be a strong temptation for the barons to cut their existing ties with Moscow and join the people. This would not be the first time this has happened. In 2020, mass protests in Khabarovsk erupted following the arrest by central authorities of Sergey Furgal, the local governor (or in our nomenclature, “baron”). Furgal, a member of the opposition party, was respected by local residents and cared about the region he governed.

This presented an acute threat to the Kremlin, especially given the distance from Moscow. As his popularity was a threat, Furgal was eventually sentenced to 22 years for murders he allegedly committed 15 years earlier. The protests eventually subsided because Moscow’s central control was still strong. It might also happen that the local baron, fearing Furgal’s fate, will prove loyal to the Kremlin.

Moscow as an Exploitive Colonial Metropolis

As long as the regime has the resources to suppress or manage crises within the empire, the situation remains calm. However, everything can change in the blink of an eye when the system is tested and proves inefficient. In the 22 non-Russian republics, such as Bashkaria and Tatarstan, ethnic issues that Moscow has tried to drown out and replace with Russian culture and language will come to the fore. While the ethnic divide will exacerbate divisions, the more significant motif is the breakdown in the Kremlin-Baron-People axis, as the entire Russian model of control rests on the vertical arrangement of power.

Fragile Power Structure in the Russian Federation

The power structure in the present Russian Federation is much more fragile than in the Soviet Union. A narrow group of individuals has replaced the Communist Party, and everything rests on the leader, from whom there is an undefined or rather absent succession mechanism. Nevertheless, in the event of the emergence of movements demanding greater autonomy or even secession, the current state apparatus will have to take countermeasures. There are essentially two options:

The Chechen Model or Violent Pacification

The most natural option is for Moscow to aggressively suppress protests, arrest the rebel leader, and make the rebellious region serve as a warning to others. The Kremlin will attempt to ethnically scapegoat the locals, portraying them as violent separatists and an existential threat to Russia and its citizens, using classic divide and conquer tactics.

The problem is that Moscow, waging a major conventional war in Ukraine, may not have the resources to decisively and demonstratively punish their rebellious province. Promoting ethnic and religious hatred would further destroy national and social cohesion and convince a large part of the Muslim population that Russia is becoming their existential threat. The risks would be enormous.

A failed military intervention of this kind would completely delegitimize the central government in the eyes of other provinces. Seeing the lack of central control, a wave of autonomous and secessionist movements would spread and become impossible to control militarily in so many places at once.

The Soft Option

Fearing such a scenario, the Kremlin elite may opt for a soft option to preserve internal cohesion and not risk the resources of their repressive apparatus. They might meet the region’s aspirations with either a broadening of autonomy or full secession, especially if it is a province of marginal importance. While this is the safer option, its effects can be exactly the same.

Other local warlords, seeing the Kremlin’s softness, may then have similar expectations, each one demanding greater autonomy or independence. Moscow would again face the same existential problem. Moreover, any submissiveness would certainly be noted within the capital city elites, and an ultra-nationalist and imperialist faction could grow in strength, demanding a hardline crackdown on the “national traitors.”

Both Response Scenarios to National Fractures Lead to Similar Results

To sum up, regional elites will conclude that the costs of maintaining loyalty to Moscow outweigh its benefits and will opt for greater regional sovereignty. Once they no longer trust the Kremlin to provide them with political legitimacy and the necessary resources, they will promote their own power base as the authentic leaders of the republics or regions. The initial rupture of the state may be limited, but in the midst of economic difficulties and political chaos, one or more federal entities may eventually emerge.

Potential New Borders and Secession Candidates

What could the new borders look like, and which regions are most likely to secede? Historically, there are many candidates. Among the nations who can prove their historical claims from before Russia’s imperial conquest are Tatars, Bashkirs, Karelians, Udmurts, Moksha, Erzia, Mari, Circassians, Balkars, Chechens, Ingush, Kalmyks, Kakhass, Altai, Buryats, Tuvans, and Sakha. A number of indigenous peoples can claim their right to self-determination under the UN Charter and the 2017 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. They will assert their rights to their traditional territories and resources, as well as administrative self-determination.

National uprisings are not a novelty in Russia. Both previous breakups were accompanied by aspirations for independence. The successful ones are known today as independent states, while others ultimately proved unsuccessful. In 1918, simultaneous uprisings broke out in Chechnya, Ossetia, and Ingushetia. At the same time, the Bashkir Republic, which the Tatars also wanted to join, declared independence. In November 1917, the Black Sea Republic was proclaimed with its capital in Novorossiysk. This was followed by the independence of Stavropol, Kuban, and Crimea as the Taurida Republic. A Siberian provisional government was also established in Tomsk.

While national and ethnic issues would certainly play an important role, they would probably not be the most vital motive for the split. A stronger rationale could be economic and social issues, meaning that secession could be sought by virtually any region that feels exploited by the Kremlin, including one with ethnic Russians as the dominant social group. This would not be unprecedented; the Ural Republic was established in 1993.